ARCHIBALD LAMPMAN (1861-1899)

by Cameron Anstee

Archibald Lampman is widely considered to be the finest of the of the Confederation group of poets whose early lives coincided with Canada’s emergence into nationhood, and who were committed to the development of a distinctly national literature for Canada. Lampman was born in Morpeth, Ontario, the son of an Anglican minister. He attended Trinity College in Toronto, and received a degree in Classics in 1882. During Lampman’s years at college, Charles G.D. Roberts published his landmark first collection, Orion and Other Poems (1880). Lampman recalled his excitement over this book in no uncertain terms: “[it is] a wonderful thing that such a work could be done by a Canadian, a young man, one of ourselves.” This assertion suggests a developing awareness of the value, and need for, Canadian literature. However, more significantly, it reminds us that the Confederation Poets were “young [men],” a fact easily forgotten given their established positions in the canon of Canadian poetry.

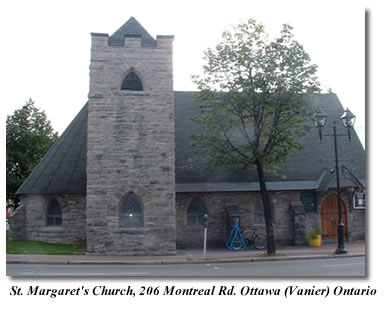

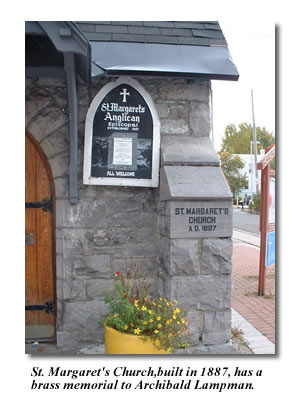

After an unhappy stint as a high school teacher in Orangeville, Lampman took up a position as a clerk in the Post Office Department in Ottawa, where he remained for the rest of his short life. The city of Ottawa provided a stimulating environment for Lampman’s creativity, both in the access to cultural events and intellectual companionship that it provided, as well as in its proximity to the countryside and the wilderness beyond. Fellow Confederation poet and civil servant Duncan Campbell Scott remembers Lampman composing his poems as he walked through the streets on his way to and from the office, or hiked through the countryside.

It is as a nature poet that Lampman has until recently been chiefly remembered. In poems like “The Frogs” and “Among the Timothy,” Lampman combines precise evocations of distinctly Canadian landscapes with a Romantic emphasis on the power of the natural world to influence the emotional state of the beholder. While Lampman felt a profound affinity with the transcendent visions of nature that he found in the work of English poets like Wordsworth and, especially, Keats, his poetry is not simply a belated imitation of Romantic models, but instead responds in complex ways to the social and intellectual currents of his own time and place. Lampman often celebrates the idea of a therapeutic nature that can console the ills brought on by the increasing urbanization of late nineteenth-century North American culture, only to discover that the green spaces of the countryside do not always heal in any reliable way the alienation of modern existence. No less important than his nature poetry are Lampman’s poems on contemporary politics and social issues: “To a Millionaire” and “The City of the End of Things” articulate a critique of capitalism and industrialization that anticipates some of the central concerns of twentieth-century writing. When Lampman died at 38 on the cusp of a new century, his work was poised between Romantic and Modernist ways of seeing the world. He published two collections during his lifetime (Among the Millet and Lyrics of Earth); at the time of his death he was working on a third, Alcyone, which was published posthumously.

It was a poem of Lampman’s, “Winter Uplands,” that provided the inspiration for the Poets’ Pathway. In giving citizens the opportunity to walk through the green spaces of their city and reflect on its literary heritage, the pathway carries on ideals that were central to Lampman’s work, which is at times ambivalent toward and disillusioned by the natural world, but is always respectful of nature’s complexity, and open to its potential to transform our lives

|