EMILY PAULINE JOHNSON (1861-1913)

by Kemisha Newman & Sarah Jamieson

One of the most famous Canadian writers of all time, Emily Pauline Johnson was born on the Six Nations Reserve in the Grand River valley, close to Brantford, Ontario. Her father, Chief George Johnson, was one of a line of hereditary chiefs who had distinguished themselves in fighting for the British in the American Revolution and the War of 1812; her mother, Emily Howells, was an Englishwoman whose father was a prominent abolitionist in the United States, and whose cousin, William Dean Howells, was the editor of the prestigious Harper’s magazine. From her parents, Johnson learned to value both sides of her ancestry: her mother introduced her to the classics of English and American literature, while her father and grandfather, themselves ardent British loyalists, also instilled in her a profound pride in her Mohawk heritage by telling stories of their ancestors. The mixing of cultural influences that defined Johnson’s family life is characteristic of her poetry and central to its political message: using prestigious English literary forms such as the soliloquy and the lyric, forms that could readily be understood and appreciated by her predominantly white audience, Johnson sought to draw their attention to the disenfranchisement of aboriginal people in Canada, whose lands were being appropriated and whose cultural traditions suppressed within a country that did not regard them—including Johnson herself-- as citizens.

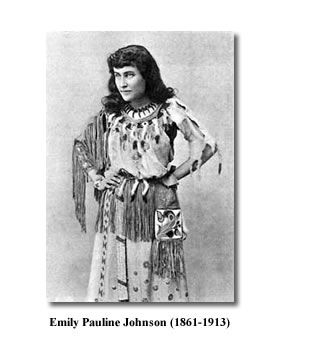

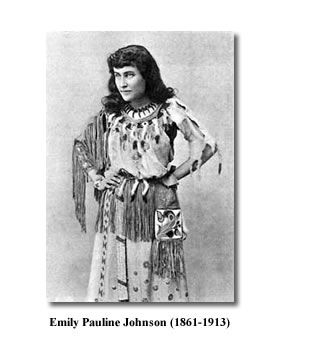

During her lifetime, Johnson was best known as a poet-performer. In an age when dramatic poetry readings were a popular form of entertainment, Johnson toured extensively between 1893 and 1909, giving riveting performances of her own works to enthralled audiences in packed houses across Canada, as well as in the United States and England. One of her most popular performance pieces was “A Cry From and Indian Wife,” a dramatic monologue in heroic couplets that provides an aboriginal point of view on the Northwest Rebellion in Manitoba in 1885, and passionately defends aboriginal land claims. Another was “The Song My Paddle Sings,” a poem that recounts the pleasures of canoeing in a fast-flowing river, and became a Canadian campfire classic. As her performance career gained momentum, Johnson developed a unique stage persona: for the first half of her show, she recited her “Indian” poems in a fringed buckskin costume of her own devising; for the second half she would change into a fashionable evening gown and elegant upswept hairstyle to recite works written in a more traditionally Romantic idiom. These costumes enhanced the contrast between what her audiences perceived as the oppositional sides of her heritage, the “savage” and the “civilized.”

Johnson’s ability to manipulate these cultural signifiers in her act indicates the complexity of her relationship with her audience, with her aboriginal ancestry, and of her position in Canadian literary culture after her death. Johnson’s critics accuse her of trafficking in the very stereotypes that she herself protests (her “Indian” costume bears more than a passing resemblance to similar outfits worn in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West shows), and her second-act switch into evening dress provided her audience with a reassuring image of the kind of assimilation expected of aboriginal people, and confirmed their assumptions of European cultural superiority. To Johnson’s defenders, these aspects of her persona demonstrate her astuteness as a performer who realized that it was only by working within the limits of audience expectation that she could make a living for herself, and hopefully get her political message across at the same time. While the controversies surrounding Johnson’s career continue to be debated, she is unquestionably one of the most compelling and original voices in Canadian post-Confederation literature.

Visually, when she performed, Johnson would start the event wearing a buckskin costume to read Indian poems before changing into an evening gown for the rest of her act. In 1886, Johnson adopted the Mohawk name of “Tekahionwake” and toured as “Mohawk Princess.”

Johnson had a complicated relationship with her audience. On her recital tours, which lasted from 1893 until 1909, she performed poetry as well as comedy in locations across England and North America. Johnson became a successful poet-performer, which enabled her to support herself and her mother. Still, she was sometimes frustrated. In 1894, Johnson wrote to her friend, Harry O’Brien to complain that she was forced to write literary pot-boilers, which are poor quality poems written quickly to make money. Basically, Johnson was complaining that her audiences wanted particular kinds of poems and as a touring artist, she was at their mercy. She struggled with this. Her lament in this letter was that she could have taught her audiences so much more if only they had been receptive.

Johnson’s literary career extended beyond the recital tours, however. She became established when two of her poems were included in the English anthology, Songs of the Great Dominion (1889). She would later publish collections of her poems and short fiction. Though famous as poet, when Johnson stopped performing, she turned her focus primarily to fiction. She was better able to support herself in part due to how well she had succeeded on her literary tours. |